Quantum Causes, Dots, and Connections

Quantum Causes, Dots, and Connections

2018 APS March Meeting

The room was enormous, filled with rows of chairs and dimly lit by lamps dotting dark gray walls. A lone podium stood in a spotlight of reflected light from a looming projector screen, and Dr. Robert Spekkens from the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics had just begun.

It was one of the opening talks for a morning session at the 2018 American Physical Society (APS) March Meeting in Los Angeles, California, and everyday notions of cause and effect were already being turned on their heads.

Spekkens laid out his principles first, explaining that two variables that are causally disconnected have no common cause, and so are statistically independent. “Learning the value of one is going to teaching you nothing about the other,” Spekkens said.

Similarly, if there’s a correlation between two variables, then there must be a common cause unless the common cause is conditional. Spekkens elaborated to say that if a common cause between two variables is conditioned on, then the two variables don’t need to be correlated and don’t have a common cause. Then Spekkens contrasted two kinds of causal systems: a classical one and a quantum one.

With only a smattering of undergraduate exposure to quantum mechanics, I was quickly lost beyond the discussion of his classical system, but this was my second day at the APS Meeting— after spending the previous day in the company of professional researchers, I was getting used to falling behind. Even so, I was determined to know more.

Spekkens was heavily engrossed in a discussion when I approached him, walking past me toward the door of the room. SPS director Brad Conrad would tell me later that same day, “Just put your hand out there, introduce yourself, and you’d be amazed at the connections and where those can lead.” I hadn’t heard that advice yet, but my curiosity was strong and I caught Spekkens’ attention with a soft “Excuse me.” He agreed to share his slides and volunteered extra links to his extended presentations on the same topic, along with a wealth of clarifying information which has continued to provide me with new insights on every reading.

Investigating the foundations of quantum mechanics was fascinating, but there was much more to see at the meeting, especially for an undergraduate student like myself.

The presentations were collected into sessions that lasted several hours and were focused on a single topic. I found myself using the program I’d been handed at check-in to narrow down interesting sessions by topic and title, and then using the APS Meeting app to read the individual abstracts. It was a surprisingly easy juggling act after the first few times.

Since I’m involved in solar energy research, I sought out sessions focused on that topic and found a few explicitly focused on quantum dots, nano-sized semiconductors that can absorb and reemit light. It wasn’t surprising that even in sessions in my general area, my understanding was quickly outstripped. Far from intimidating, though, it was inspiring.

One such presentation was by Professor Ted Sargent from the University of Toronto on quantum dot sensor development. A success from his team’s research was later used in certified devices. Without a sufficient background in quantum dots, his finer points were obscure to me, but it remained one of the most memorable presentations I attended.

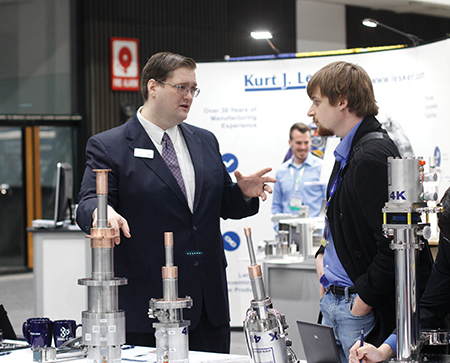

Between sessions, I visited the graduate school and job fair. Each school and company had a booth, and the colorful displays sported pens, cards, and an assortment of trinkets with logos and contact information printed on them.

It was there that I met SPS director Brad Conrad. He was filled with infectious enthusiasm, telling me that the March Meeting is one of his favorite meetings of the year. “When you start coming year after year, you not only see your friends from undergrad but your friends from grad school, you see your colleagues, post-docs, and you get to see these people through a wide cross-section of the community. So, the nice thing about the March Meeting is that it’s like a family reunion,” Conrad said.

This piqued my curiosity—since he’d attended so many, I asked what he thought of the presentations this year. His reply was unhesitating. He explained he’d been at the undergraduate sessions previously. “They were the best yet,” Conrad said. It was an easy segue into a discussion about advice for undergraduates like myself attending the meeting without the level of expertise of so many other attendees.

“The most important thing you can do at the March APS Meeting is meet people,” Conrad said, explaining that the meeting isn’t just for learning new things in the presentations, but also for making connections.

It was advice that I quickly experienced firsthand. Within moments of admitting that I study journalism as well as physics, Conrad was introducing me to Julia Majors from the American Institute of Physics News and Media Services team, asking her to share some insight into the field of science communication with me. It was a delight to discuss a field that overlapped with my current studies and interests—especially since Majors was passionate about her work. When she invited me to observe a press conference I eagerly accepted.

It was little different from the staged press conferences in my tiny undergraduate classroom back home, with tripods, cameras, lights, and microphones scattered around a small, quiet room filled with chairs, a few tables, and a single podium. It was unassuming and simple, and I was wholly enamored with it. I watched silently as scientists presented featured research projects in a panel session. With only two minutes left to spare, I finally left to meet my friends for the final presentation of the day, where I proceeded to bombard them with details until the session began.

It was only the end of the second day, but from twisting my mind around cause and effect in a quantum world and nanomaterials exceeding my depth of experience, I was as exhausted as I was exhilarated—eager for whatever the next day might hold.