Accessing My Creativity App

Winter

2015

Pathways - Advice from Experienced Voices

Accessing My Creativity App

A Theorist’s Journey Through Supersymmetry

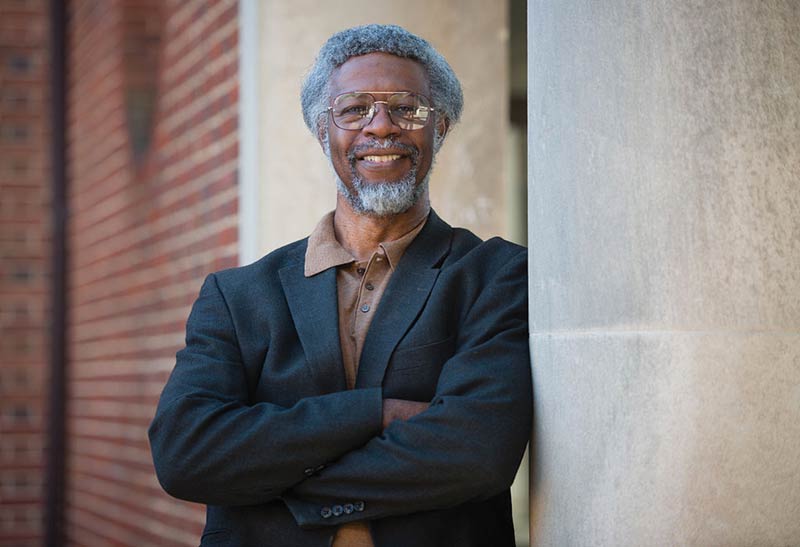

By:Sylvester J. Gates, Jr., Sigma Pi Sigma Honorary Member, John S. Toll Professor of Physics, University of Maryland in College Park

One hundred years ago, Einstein completed his theory of general relativity. It was a feat of imagination, and, as Einstein himself said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

One hundred years ago, Einstein completed his theory of general relativity. It was a feat of imagination, and, as Einstein himself said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

In honor of this anniversary, it is my very great pleasure and honor to share with the SPS family my own thoughts about how imagination can be a source of creativity in physics. As I am only a “simple country theoretical physicist,” not a neuropsychologist or psychologist, I can share only my own experiences.

Physics is the only piece of magic I have ever seen in the real world. Its incantations are written in mathematics. People often share with me their creative ideas about issues at the frontiers of theoretical physics, ideas that often challenge Einstein’s. The problem with most of those proposals is that their authors do not recognize the importance of having an appropriate mathematical perspective. Even Einstein first obtained a PhD before he dazzled the world with his deep insights about nature.

As a mathematical physicist, I spent my younger years building that foundation. It allowed me to use what I call my “creativity app,” the capacity for creativity that lies within all of our minds. I have focused mine on the subject of supersymmetry. It has long been my hope to discover a piece of magical mathematics in this area.

Booting Up the App

One early indication of my creativity occurred when I was four years old and living on a US military facility, named Pepperrell, near St. John’s, Newfoundland in Canada. My family went to see a science fiction film, ‘‘Spaceways.’’ That evening, according to family lore, I attempted to explain how rockets worked to my dad! As a child I loved to draw rockets, ships, and airplanes, of my own imaginative designs. These sketches included cut-away views showing what their interiors were like.

On March 27, 1962, my mother died. This was, of course, an enormous, almost overwhelming tragedy for a child to face. Driven by this to a large extent, I retreated throughout my teenage years into the world of my imagination, of science fiction and comic books. My favorite superheroes included scientists such as Reed Richards of the Fantastic Four. These figures inspired me.

In the fall of 1967, I took my first physics class. For years I had been using my imagination to build worlds within my head. In this class I saw how mathematics allowed people to build tiny portions of the real world within their heads. That astounded me.

In my first year at MIT, I learned calculus. I had always been good at math, but it was calculus that made me pointedly aware of my creativity app. My experience showed me a portion of my subconscious capable of interacting with my conscious rational mind to produce solutions to mathematical problems. This may sound mystical, but I am sure it is what is meant by the idea of a “muse” in other areas of human creativity.

Listening for Cat Paw’s Footfalls in the Mist

Once one has experienced one’s creativity app, being able to notice subtle discord becomes important. This was clearly Einstein’s great ability. Anyone who had studied Newton’s classical physics and Maxwell’s equations could have spotted the tiny incompatibility between the two with regard to their implications about the behavior of space and time. It took the genius of Einstein to fully realize the significance of this incompatibility. It also took his commitment to transcend what he likely would have said was “traditional thinking” and today we call “conventional wisdom.” One must make an absolute commitment to avoid being swept along by the crowd and be willing to take the chance to tread mathematical pathways others avoid.

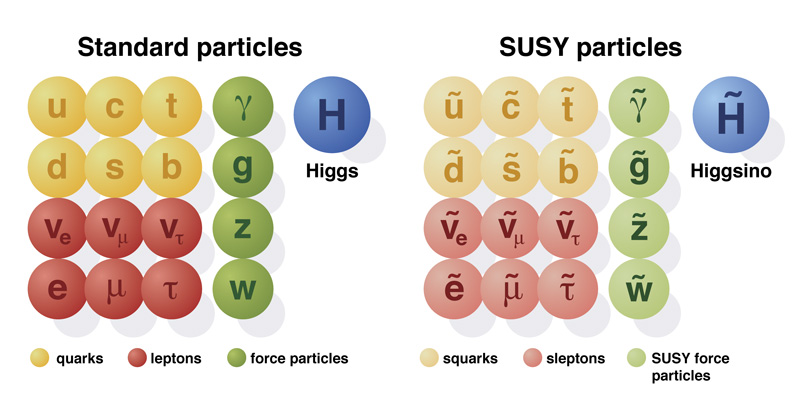

As I mentioned before, I have long hoped to discover a piece of magical mathematics related to supersymmetry (SUSY). I hoped it would accurately describe something buried deep in nature. SUSY is not a single model any more than Newton’s second law is a rule that applies solely to falling apples. Instead, SUSY is a framework for many models breaking the rule that all matter particles are fermions and all carriers are bosons. It relates each standard model particle to a new form of matter and energy called a “superpartner.”

With many different sets of equations that incorporate supersymmetry, how do we pick the right ones? In the last decade of my work, it seems possible I may well have found a way forward. A group of my colleagues and I have been studying "adinkras," a term we borrowed from West Africa that originally referred to visual symbols used to represent concepts. For us, an adinkra is a graphical representation reminiscent of genomic structures that precisely encode the mathematical relations between the members of supersymmetry families. It could help us to ensure that the SUSY property is made manifest at every stage of calculations involving the quantum behavior of these equations.

While a composer’s work is judged by the nature of the audience, a theoretical physicist must be judged by the audience of nature. As revealed by experiments and observations, nature is the final arbiter.

Particle colliders have found no evidence yet in favor of SUSY. But such searches can strive only to observe the predictions of models. Even under many reasonable assumptions, numerous such models remain possible. Ruling out one or a few does not exclude a far greater multitude of others.

Even at the age of 65, I do not know if I have succeeded in my personal quest to understand the subject of supersymmetry at its deepest levels. But such strange possibilities, arising from my apparently still functioning creativity app, excite me. They make the experience of being a theoretical physicist a great joy for me. //